Lumber Camp Cook

Rita Poirier Chaisson was born in 1914 on Canada’s Gaspe Penninsula. In 1924, her father Paul Poirier, a lumberjack, moved the family to the North Country where logging jobs were more abundant. Her mother agreed to leave Canada with reluctance. The Poirier family spoke French, no English, and she was convinced that New Yorkers “just talk Indian over there.”

The family kept a farm near Tupper Lake, with as many as 85 cows. Rita planted potatoes and turnips and helped with the haying. She and her siblings attended a local school, where she was two years older than most of her classmates. Although she picked up English quickly, her French accent made integration difficult. She left school at the age of 14, and worked as a live-in maid, cooking and cleaning for local families for three dollars a week. She used her earnings to purchase clothes by mail order for her sisters, mother, and herself.

At 17, Rita married a lumberjack with whom she had five children. The family moved to New Hampshire for a brief period, but Rita left “because the kids didn’t like it.” The marriage fell apart, and Rita raised her children in Tupper Lake as a single mother.

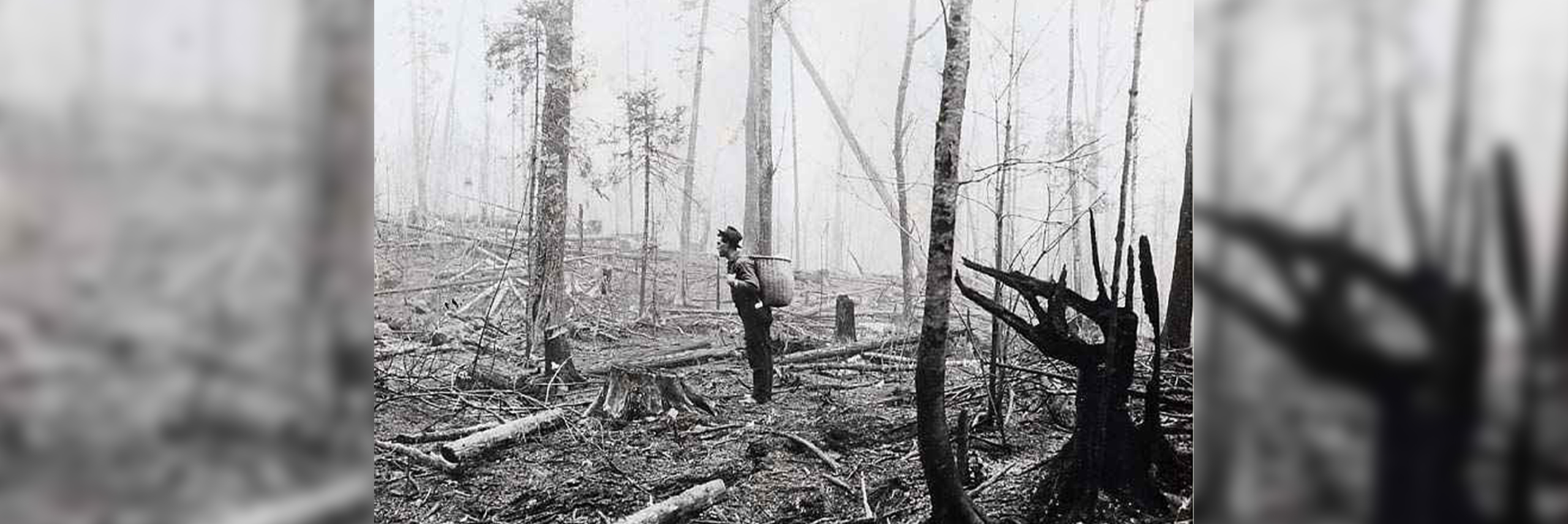

To make ends meet, she took work as a cook in lumber camps, moving around from camp to camp. In summer, she cooked for men cutting softwood and at another camp in winter where the men harvested hardwood. Working May through February, she was forced to rely on unemployment benefits to get by in March and April. Her children stayed in town while she was in camp during the week, cared for by friends and family, spending summers with their mother and the jacks in the woods.

As the only woman for miles, Rita preferred working in camps with separate buildings for the kitchen and sleeping quarters. Although she always had her own room, if the men were in the same building the odor of unwashed clothes and bodies permeated everything. Some of the men chose not to walk to the outhouse when it was cold at night, instead of using a designated spot at one end of their bunkhouse.

Smells aside, Rita was always on good terms with the men, and the jobber always made sure that she had no problems. At Christmas, each man gave her a dollar. Only once was she propositioned, by a young man who asked “Hey cook, you wanna go out tonight?” Rita responded that “if I’m gonna go out, I’m gonna go out with a man, I’m not gonna go with a kid.”

Rita worked for smaller outfits because she didn’t want to cook for more than 35 men at a time. As it was, she maintained an impressive schedule: up at 4 am, serving breakfast at 6, usually with bacon and fried potatoes, pancakes, toast, and fruit. She served lunch at 11:30. If the men were staying out all day, she’d pack them lunches. The last meal of the day, at 5:30, usually included steak, roast beef or pork, cabbage, and bread. Cooking in-between meals, Rita often made 7 pies, 2 batches of cookies, 2 cakes, and as many as 500 doughnuts and 8 loaves of bread each day. She never went to bed before 8 or 8:30.

Adirondack lumberjacks earned their pay- it was heavy physical labor. As a camp cook, Rita was responsible for filling their plates well. She recalled that “they worked hard and the weather was cold so I always made sure they had good meals… of course, I had to plan everything ahead to make sure I had time to cook everything. We only had wood stoves then, you know.”

Meals were eaten in silence. A sign in French and English was posted at the entrance of the dining hall indicating that no talking was permitted. The men were hungry, and ate as though “they were starved to death!” During meals, Rita made sure that each lumberjack had enough of everything, walking between the long tables with a fresh pot of coffee and placing condiments at regular intervals along the tables.

Rita worked for the most part without written recipes. She collected a few by cutting them from the backs of macaroni and raisin boxes. She made macaroni salad with instant and evaporated milk, and “the men went wild with that.” Another popular dish was one she composed of homefries and hot dogs ground together and fried in pure lard. Cauliflower “with a nice milk gravy” was “out of this world.”

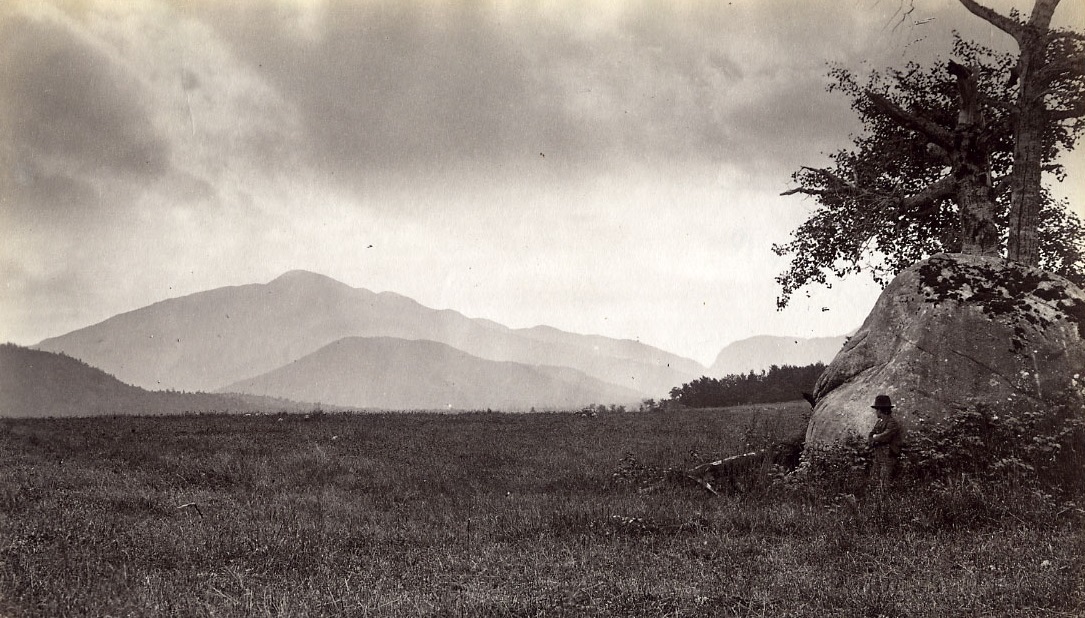

Working long days in isolated camps miles back in the Adirondack woods, Rita had little time to form friendships but “I never had time to be lonely.” There were other compensations: “Oh, the smell of the pine. And the air was so fresh. You’d wake up in the morning… oh, my God, you felt like a millionaire.”

Rita retired from camp cooking after 20 years. She worked into her eighties, taking in laundry and selling second-hand clothing from her home. In the late 1980s, she spoke to a reporter saying, “Those 20 years in the woods were some of the best in my life. The only problem I’ve had since retiring is trying to break the habit of cooking for an army.”

In 1996, a folklorist interviewed Rita Chiasson about her life. The tape and a typed transcript are in the collection of the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake.