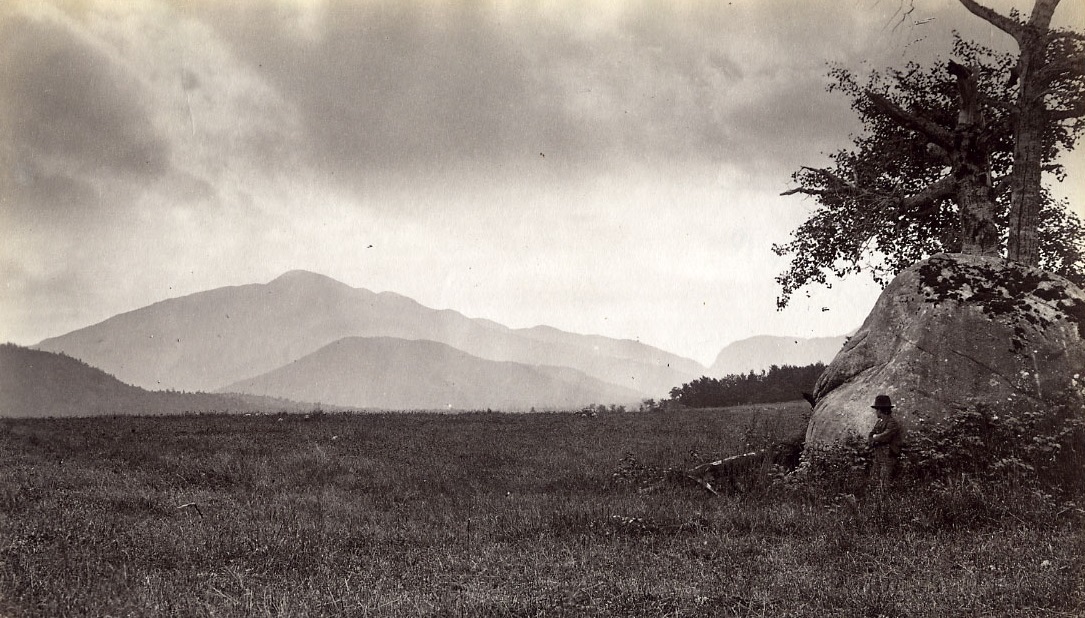

Mining in the Adirondacks

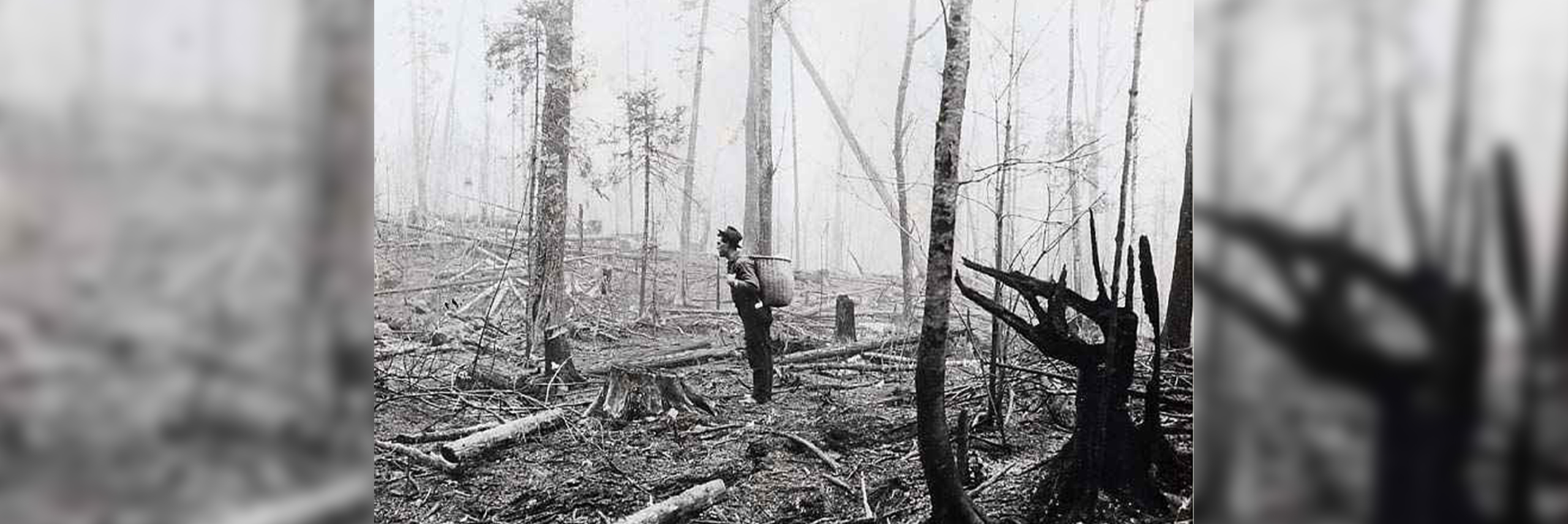

Most visitors to the Adirondack Park are unaware that mining was once a major industry and employer in the region, or that it brought an ethnically diverse population of workers into the Park. At places like Tahawus and Mineville, once enormous industrial sites, are slowly being reclaimed by nature, hidden by wilderness. The history of Adirondack mining— and of the people who lived and worked in its shadow— has become largely invisible.

Company employment records document French-Canadian, Spanish, Irish, Lithuanian, Russian, Columbian, German, Argentinean, Welsh, Italian, Norwegian, Hungarian, Syrian, Swiss, Japanese, and Finnish miners working alongside their American-born (white, black, and Native American) counterparts in Adirondack mines.

Company recruiters brought new immigrants right from the docks of New York City to the Adirondacks. In larger company towns, as each new immigrant group arrived, the more established miners moved up, occupying supervisory positions and better housing. Newer immigrants were assigned the least desirable and most hazardous jobs.

A sense of community could be difficult to create and maintain, and small Adirondack mining towns often experienced the ethnic discrimination and violence more commonly associated with larger, urban areas. Companies like Witherbee-Sherman designed their towns with ethnically segregated housing— exacerbating tensions between old and new immigrant groups— which served to reduce the chances of miners finding common cause and striking, or, worse, unionizing.

In the late 19th century, established Irish mine workers, many of whom had graduated to supervisory positions, occupied the most comfortable company housing. New, poorer immigrants were assigned to multi-family tenements. Abuse was common: Irish foremen told their Italian workers they had to pay for their own tools (which the company actually provided at no cost) and imposed pew rents in the local parish that new immigrant workers could not afford. The Italian “La mano nera,” (the Black Hand), engaged in arson, intimidation, and extortion, terrorizing Moriah in the early teens.

To ease tensions and relieve boredom, mining companies sponsored baseball teams, mother-daughter dinners, card parties, dances, and holiday parties. Alice Hooper Tibbets recalled “hayrides and sleigh rides under the stars, births, Christenings, weddings, funerals, sewing bees, amateur plays, Easter egg hunts, political meetings, morning prayers… war-time speeches, card games, and… musical entertainment, with an organ, a violin, a harmonica, and bone rattling.”

Many Adirondack mining towns have disappeared or are greatly diminished, but the ethnic diversity mining brought to the region remains. Names like Calabrese, LaBier, Farrell, Donahue, Emru, Fagerberg, remain part of the Adirondack community. Food traditions, like French-Canadian meat pies and German sauerkraut, are recognized as regional favorites.