Spring Pests

Enduring black flies is a test of anyone’s character. The ways in which people have coped with the months of May and June and these unwelcome spring arrivals have been extensively documented. There is even a black fly song!

May in the Adirondacks typically brings sunshine, warmer days, green grass, tree buds, daffodils… and the black flies.

Anyone who has spent time in the Adirondacks during the spring is aware that black flies have defined the season for as long as anybody can remember. During the nineteenth century, as recreational visitors began to enter the region, it was apparent that a remedy had to be found to ease the annoyance of the little determined bugs.

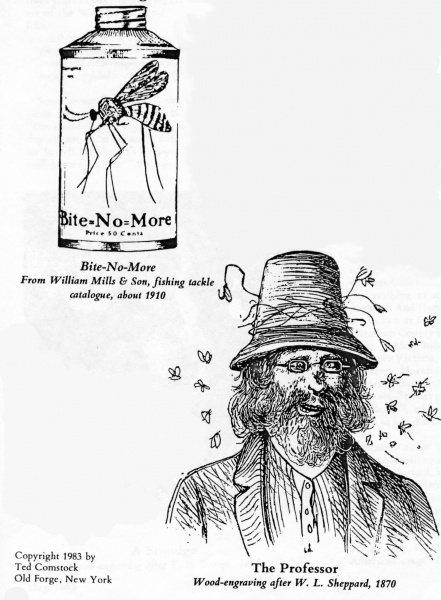

Countless repellents and home solutions have been invented to help discourage black flies. Just about any concoction, you can think of has been tried to relieve the nuisance of these pests (some a little more sophisticated than others).

George Washington Sears, better known by his pen name “Nessmuk,” recommended “a good, substantial glaze, which [he was] not fool enough to destroy by any weak leaning to soap and towels.” (Adirondack Life, May 1992) While probably effective, it may be best to travel alone when testing this remedy.

Another solution that may not always be practical but was sure to keep flies away was a smudge; a small fire intended to produce large amounts of smoke. Some, especially those native to the area, aimed at simply ignoring the bugs. However, when all else failed whiskey was not an uncommon aid in tolerating the pests.

Following the Civil War, the Adirondacks became a popular tourist destination, due to the inspiration of the Reverend William H.H. Murray’s book, Adventures in the Wilderness, published in 1869. These tourists were not used to “roughing it” and as a result, a greater need for bug repellent arose.

However, Murray himself would have his readers believe there was no bug problem in the Adirondacks and that there certainly was nothing to worry about when it came to black flies. He wrote of black flies as “one of the most harmless and least vexatious of the insect family…The black fly, as pictured by ‘our Adirondack correspondent,’ like the Gorgon of old, is a myth, — a monster existing only in men’s feverish imaginations.” (Adventures in the Wilderness, 56)

Despite Murray’s claim, black flies were a vexing problem from which people sought relief. Early repellants followed recipes that included anything from an ointment of petroleum to combinations of any of the following ingredients: castor oil, tincture of iodine, Vaseline, ammonia, kerosene, oil of peppermint, olive oil, turpentine, oil of tar, pine tar, or oil of cedar, to name a few. (Adirondack Life, May 1983)

Bug nets also emerged as a way to keep the pests away. Fine meshed nets covered the head and kept black flies from landing and biting. Today this solution has evolved and expanded to include improved fabric for tents and clothing to add extra relief.

Currently, DEET-based repellents are popular, however, there has been a shift towards using natural-based recipes with fewer harsh ingredients. Some people choose to also avoid wearing colors such as blue, purple, and red, which seem to attract black flies.

There has also been research into ways to prevent black flies before they have the opportunity to become pests. In 1982, testing of a new treatment known as Bti (Bacillus thuringensis israelensis) began in the Adirondacks. Many see this treatment as the best alternative to the previous method of aerial chemical insecticide spraying.

Bti treatments have proved to be an effective organic method targeting only the black fly larvae. However, it is a time-consuming process that involves careful study, trained technicians, and intensive work schedules in order to ensure successful treatment of streams and rivers at a precise point during the larva stage. It is quite costly. In 1988 there were only six towns in and around the Adirondacks that had adopted the treatment, by 2002 the number had grown to twenty-nine.

While some towns have adopted Bti treatments, there are still many areas that have not. The Adirondack Park, after all, covers six million acres of forest, lakes, and rivers. The black fly continues to plague many regions, requiring visitors and residents alike to use commercial “bug dopes” or some of the old-time methods described above in order to survive the season and simply hope for hot weather and the end of black fly season.