The Trudeau Sanitorium Diet

In Rules for Recovery from Tuberculosis, published in Saranac Lake, New York, in 1915, Dr. Lawrason Brown stated that “there are no more difficult problems in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis than to make some patients gain weight and to help others avoid digestive disturbances.”

Diet was an important part of treatment for tuberculosis, the “white plague.” Highly contagious, tuberculosis (or TB) was one of the most dreaded diseases in the 19th century. Caused by a bacterial infection, TB most commonly affects the lungs, although it may infect other organs as well. Today, a combination of antibiotics, taken for a period of several months, will cure most patients.

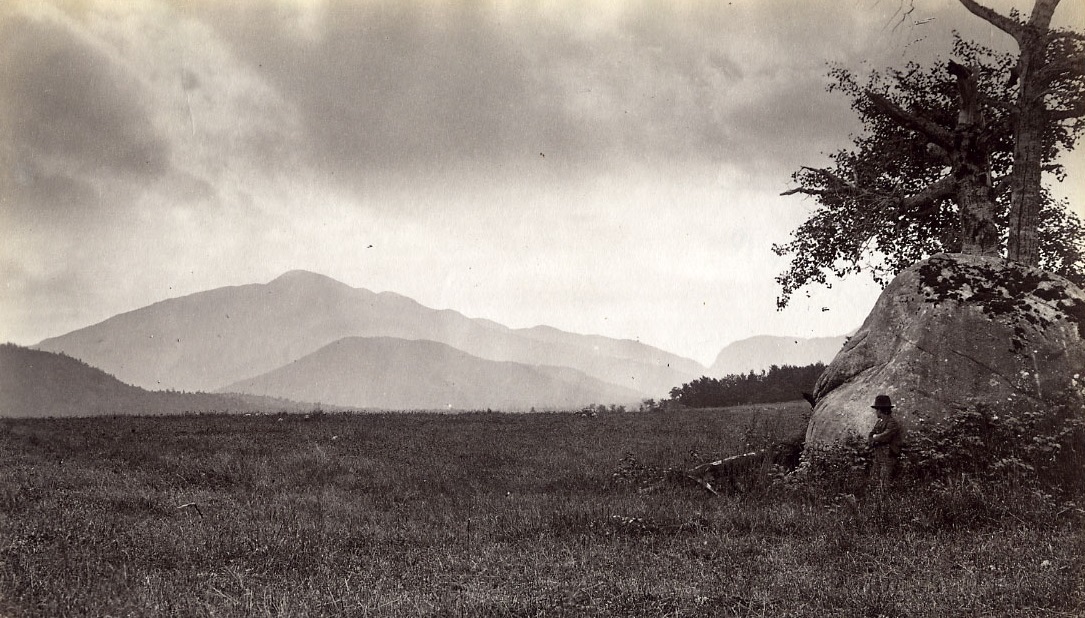

The drugs used to treat tuberculosis were developed more than fifty years ago. Before then, thousands came to the Adirondack Mountains seeking a cure in the fresh air, away from the close quarters and heat of urban streets. Doctors prescribed a strict regimen of rest, mild exercise, plenty of fresh air, and healthy, easy-to-digest meals.

Patients were encouraged to spend as much time as possible out of doors. The lungs, it was reasoned, responded well to a regular intake of fresh air. The sleeping porches that characterize the architecture of Saranac Lake were designed to “enable a patient to remain out of doors . . . so much that it has been called the ‘twenty-three-hour treatment.'” Patients often spent most of their days outside on a chair or bed, sleeping on open-air porches at night, well bundled up against the Adirondack cold.

One of the characteristic symptoms of the disease is unexplained weight loss. To boost the patient’s strength and ability to fight the disease, his or her weight was monitored daily, along with the level of appetite and food intake.

Dr. Brown, a leading physician and member of the medical team at the Trudeau Sanitorium in Saranac Lake, wrote, “It is an old adage among patients with tuberculosis that they should eat once for themselves, once for the germs, and once to gain weight . . . not only must three good meals but six glasses of milk and six raw eggs be swallowed every day.”

A suggested schedule for a patient’s day included milk on waking in the morning, followed shortly by breakfast; a light mid-morning meal, dinner from 1:00 to 2:00, followed by supper at 6:00, and another light meal just before bed. Patients were encouraged to eat a small meal one-half hour before and one-half hour after taking exercise.

The house rules for the Trudeau Sanitorium specified that breakfast was served in the dining room between 7:30 and 8:30 each morning, and “NO ONE MAY ENTER AFTER THAT HOUR.” Patients were permitted to invite friends for meals, as long as they registered them at the administration desk at least one hour before the meal was served. Conversation about one’s disease, symptoms, “or any subject relating to illness is discouraged, particularly during meals.”

The rulebook also stipulated “only pasteurized milk should be consumed by patients.” Those wishing to purchase milk to drink between meals were provided with a list of local dairies offering pasteurized milk for sale.

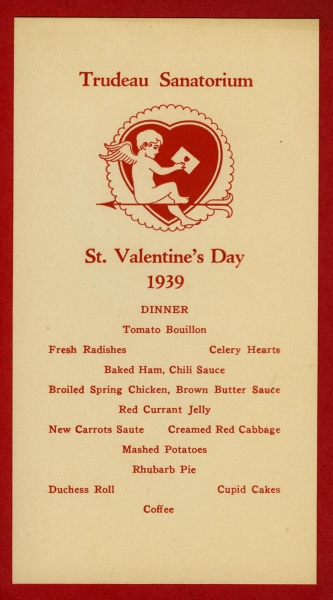

In spite of the regimentation of institutional life, meals were a social occasion, and holiday meals an important part of community life at Trudeau. Christmas, Easter, New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving, St. Patrick’s Day, Washington’s Birthday and Valentine’s Day all featured special menus served with a festive flair.

The New Year’s dinner in 1926 included fried filet of sole with tartar sauce, braised tenderloin of beef with Béarnaise sauce, roast Maryland goose, apple sauce, creamed onions, sweet potatoes glace, endive salad, mince pie, tutti frutti ice cream, assorted cakes, fruit basket, cider, and coffee. Easter dinner, 1921, featured lobster Newburgh, roast lamb, and roast chicken with stuffing. The evening meal on Washington’s Birthday included, of course, cherry pie.