Adirondack Spring Water

The Adirondack Mountains have long been treasured for the healing properties of clean air, beautiful scenery, and sparkling water. The air and scenery could only be experienced in the Park itself, but water could be bottled and shipped elsewhere and became a major export from the region during the 19th century.

Urban-dwelling New Yorkers in the late 1800s suffered from the effects of overcrowding, poor ventilation, summer heat, and the stresses of working a nine-to-five job. New ills like “dyspepsia” and “neuralgia” could be alleviated with a healthful escape to the Adirondack Mountains, where fresh air, exercise, and pure water would restore the weakest constitution to vigorous health.

For those who could not afford the time or cost of summer in the mountains, bottled water from Adirondack springs was a more affordable alternative. Bottled water, some imported from overseas, was served in fine restaurants in New York City. Bottled from mineral springs, it often contained slight amounts of sodium bicarbonate, which could soothe an unsettled stomach. Bottled water was valued not only as an aid to digestion but also for other perceived medical benefits.

In the early 1860s, the St. Regis Spring in Massena, New York, produced water advertised as a “curative for all affections [sic] of the Skin, Liver and Kidneys.” Harvey I. Cutting of Potsdam bottled and sold “Adirondack Ozonia Water,” the “world’s most hygienic water” from a spring “in the wildest portion of the Adirondack wilderness, far from the contaminations of human habitation” near Kildare in St. Lawrence County.

Cutting’s advertising included testimonials from satisfied customers. G.W. Schnell, a wholesale grocer in Indianapolis, Indiana, wrote in 1905, “I have used your Adirondack Ozonia Water for several months and find it to be the best water I have ever had. It acts on the kidneys and bowels in such a way as not to be annoying.” With typical Victorian hyperbole, the company touted the water’s “most excellent medicinal qualities,” claiming it cured hay fever, “congestion of the brain and prostate gland,” breast cancer, rheumatism, inflammation of the bladder, Bright’s disease, and “stomach troubles.”

By 1903, the Malone Farmer reported “an average of 1,500 gallons of Adirondack water is shipped from Lowville to Watertown each week. The water is sold in that city in three-gallon cases at 15 cents per case.” In 1911, the Ogdensburg Advance and St. Lawrence Weekly Democrat ran a story in the Farm and Garden column advocating “Water as a Crop,” as “a great many cities are complaining of the inferior quality of the water furnished by city waterworks.” Water wagons, bearing loads of spring water, were a common sight in many cities, and a “profitable trade in bottled water could be worked up at a little cost to the farmer, provided, of course, they have never-failing springs of pure water from which to supply the demand.”

- Augustus Low (1843-1912), was a prolific inventor, entrepreneur, and owner of the Horse Shoe Forestry Company in northern Hamilton County, near the center of the Adirondack Park. Low-produced lumber, maple syrup, wine, and jams and jellies. In the 1880s, his company began exporting bottled water from the “Adirondack Mt’s Virgin Forest Springs.” In 1905, Low designed and patented a glass water bottle with heavy ribs near the neck that strengthened it, reducing breakage while in transit. The ribbing also made the bottles easier to grasp.

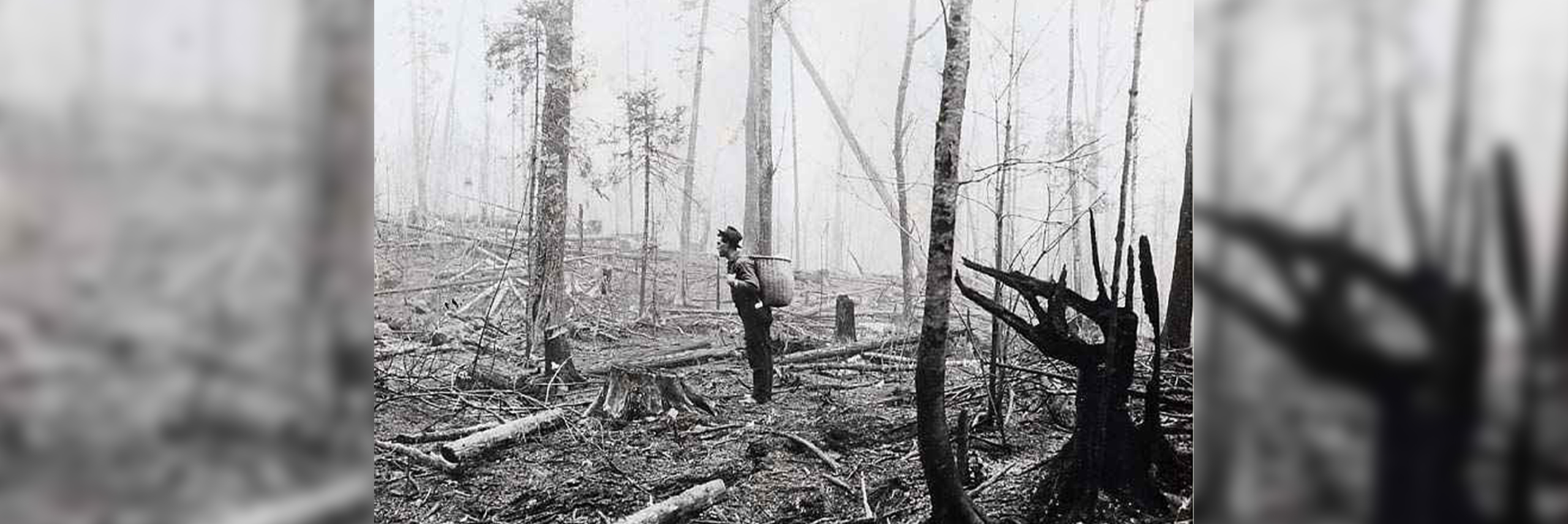

In 1908, Low’s Adirondack empire collapsed when a series of devastating forest fires burned through his Adirondack properties. The Adirondack Museum owns several objects relating to the Horse Shoe Forestry Company’s products, including one of Low’s spring water bottles and the patent he received for its design.