Advice on Eating in Camp

Enjoying a meal around a campfire is an important part of an outdoor experience. Many a camper insists that food just tastes better when eaten outside.

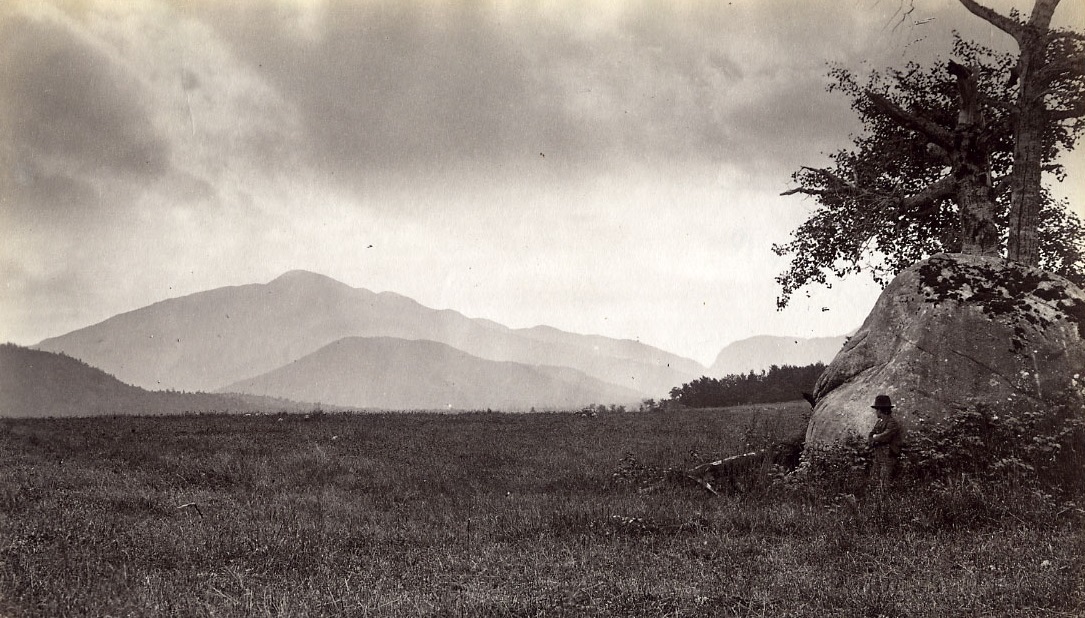

An anonymous sportsman wrote about his trip to the Adirondacks in 1867, with particular mention of meals: “Trout ‘Flapjacks’ & corn cakes were soon cooked… and then we hurried into the Tent to eat, for the Mosquitos were very troublesome outside, & threatened to devour us, waving [sic] all objections as regarded our not being Cooked. The next morning we were up early & had such a Breakfast. Venison nicely cooked in a variety of ways great blooming Potatoes, splendid Pancakes with maple sugar syrup, Eggs, & actual cream to drink… We could scarcely leave the Table…”

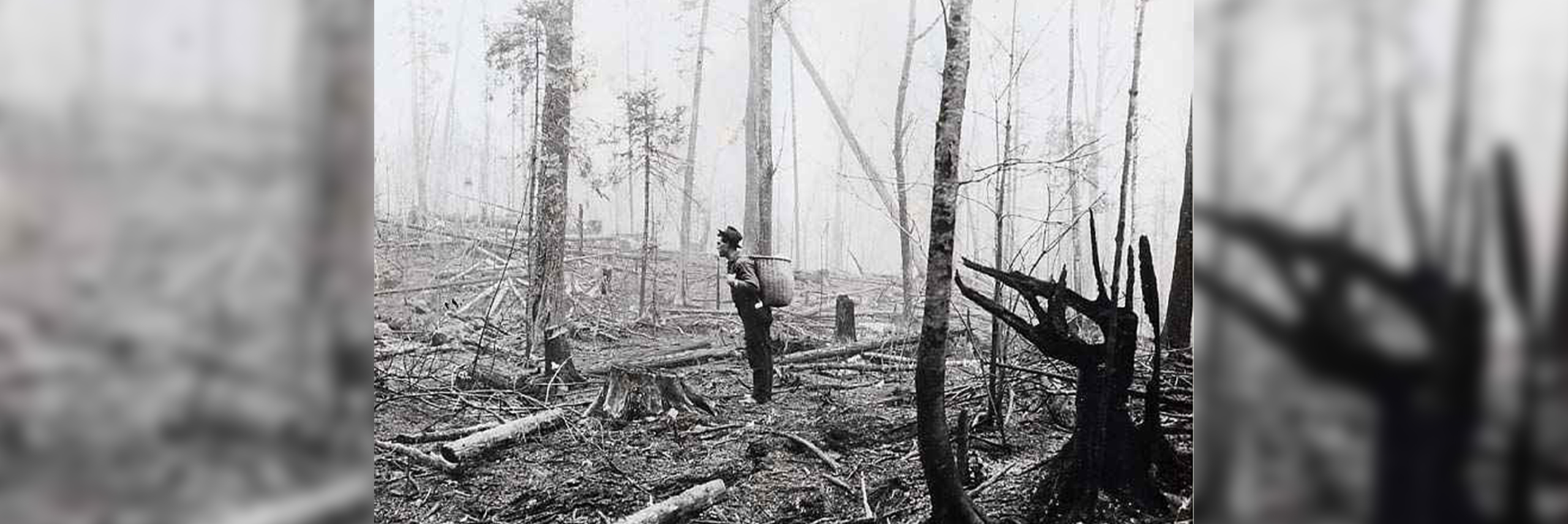

Cooking outdoors can be as much fun as eating, but for those who prefer the comforts of modern appliances, it may present a challenge. Thousands of guidebooks have offered advice and recipes to would-be Adirondack camp cooks for more than a century.

In 1869, William H.H. Murray inspired thousands of novice sportsmen to try their hand at camping in the Adirondack Mountains. His book Adventures in the Wilderness offered advice on how to get there, what to wear, how to find a guide, where to hunt and fish. His suggested list of provisions was basic: “All you need to carry in with you is Coffee, Pepper, Tea, Butter (this is optional), Sugar, Pork, and Condensed Milk… If you are a ‘high liver’ and wish to take in canned fruits and jellies, of course, you can do so. But these are luxuries which, if you are wise, you will leave behind you.”

Murray insisted, “I do not starve” while living in the woods. His Adirondack diet consisted primarily of potatoes (“boiled, fried, or mashed”), venison in various forms, trout, pancakes, bread (“warm and stale”), coffee, and tea.

Nearly a half-century later, Horace Kephart wrote The Book of Camping and Woodcraft. Kephart’s intended audience was male sportsmen traveling in a small group for an extended stay in the woods. He offered “ration lists” for each season, for four men on a two-week stay, for heavy and light meals. The amount of food listed would have given Murray pause. Salt pork, canned corned beef, fresh eggs, butter, cheese, lard, rice, macaroni, flour, onions, beans, canned tomatoes and corn, coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, maple syrup, dried fruit, raisins, canned peaches, shelled nuts, and a lengthy list of condiments could be hauled to camp in lightweight chests or pine grocery boxes. He also recommended bringing a cookbook.

Kephart advised his readers that “poor cookery is not so much the result of inexperience as of carelessness and inattention to details… A bad mess is sure to follow from (1) a poor fire, (2) seasoning too much or too early in the game, (3) too little heat at the start, or too much thereafter, (4) handling or kneading dough made with baking powder; and it is more likely than not to result from guessing at quantities instead of measuring them.”

His recipe for oatcakes: “Mix ½ pound of oatmeal, 1-ounce butter, and a pinch of salt with enough water to make a moderately thick paste. Roll to a thickness of 1/3 inch, bake in frying pan, and give it to a Scotchman- he will bless you.”

Although authors J.C. and John D. Long reassured insecure camp cooks in the 1920s that “after the camper has been out for a week he will almost be able to eat, like, and digest gravel,” they also underscored the importance of meals to the outdoor experience: “To the average person much of the enjoyment of …camping will depend upon the quality of the meals that are supplied. If the day be started with a good breakfast of steaming coffee, a rasher of crisp bacon with hot flapjacks and crisp fried potatoes, the day is well begun and everything else is likely to pass off delightfully. But begin with dishwater coffee, lukewarm in temperature, soggy, half-done flapjacks, soft, stringy bacon and limp, greasy potatoes, and the rest of the day will be equally distasteful.”

The Long’s 1923, book, Motor Camping, included detailed instructions for making a fire, maintaining a balanced diet, a description of essential food supplies, and suggestions about where to purchase groceries while on the road.

Their recipes, written for campers traveling by car, were simple by today’s standards but involved more ingredients and more perishables than Murray could have recommended. Heavy jars and cans, provided they were packed to avoid breaking, were easy to transport in an automobile. Camp stoves fueled by oil, gas, kerosene, or solidified alcohol provided alternatives to cooking over an open fire. Groceries were available for purchase at roadside establishments that sprang up across the Adirondacks to cater to the motoring public.

The Longs anticipated that most campers, regardless of nearby grocery stores, would procure at least some of their food in much the same way that 19th-century sportsmen had done. Their cooking instructions include recipes for fish and small game, particularly squirrels: “Squirrels should be broiled, using only young ones. After skinning and cleaning, soak in cold salted water for an hour. Wipe dry and place on a grid with slices of bacon laid across for basting. To fry old ones, parboil slowly for half an hour in salted water and fry in fat or butter until brown.”