An Adirondack Presidential History

On the damp night of September 14, 1901 Vice President Theodore Roosevelt made his legendary night ride from the Adirondack Mountains to the Presidency of the United States of America. While Roosevelt’s first ascension to the post was not the result of being directly elected president, assuming the position as the result of the assassination of President William McKinley, he would go on to be elected for a second term in his own right.

Though the U.S. election of 1900 was far different than the televised spectacles we see today, the campaign trail was just as grueling. In a time before sound bites and private jets, some candidates spent an exceptional amount of time traveling the country carrying their message to voters. In fact, by November 3, 1900 Roosevelt had given more speeches and traveled further than any candidate in the nineteenth century, presidential or vice-presidential, with the exception of William Jennings Bryan four years earlier. However, in 1900 Bryan could not match Roosevelt’s travel and time on the campaign trail. In a quarter of a year, Roosevelt made over 673 speeches, at 567 towns, in 24 states, traveling over 21,000 miles.*

Roosevelt’s tireless campaigning, combined with the nation’s booming economy and the success of the Spanish-American War, led to McKinley’s easy re-election with Roosevelt as Vice President. However, during this term McKinley would not fulfill an entire year of service as president. On September 6, 1901, while visiting Buffalo, New York for the Pan-American Exposition, the president was shot at the Temple of Music while attending a reception. A man named Leon Czolgosz, whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief appearing to be a bandage that was actually covering up a revolver, shot McKinley twice, once in the chest and once in the abdomen. Buffalo newspapers later described Czolgosz as either “a lunatic or an anarchist.”

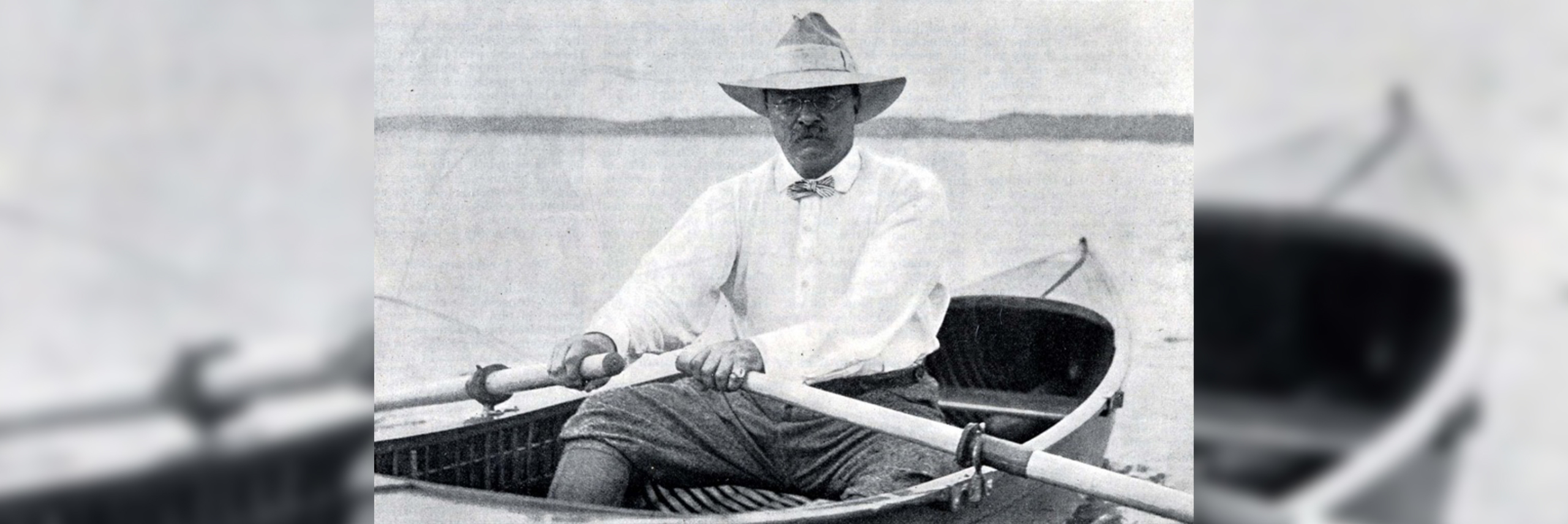

Initially, it appeared that McKinley would rally from his wounds. While Roosevelt traveled to the president’s bedside from a luncheon at the Vermont Fish and Game League on Isle La Motte, on Lake Champlain, by the 10th of September the president made great improvements and Roosevelt’s presence was no longer required. To reassure the public, it was advised he leave Buffalo.

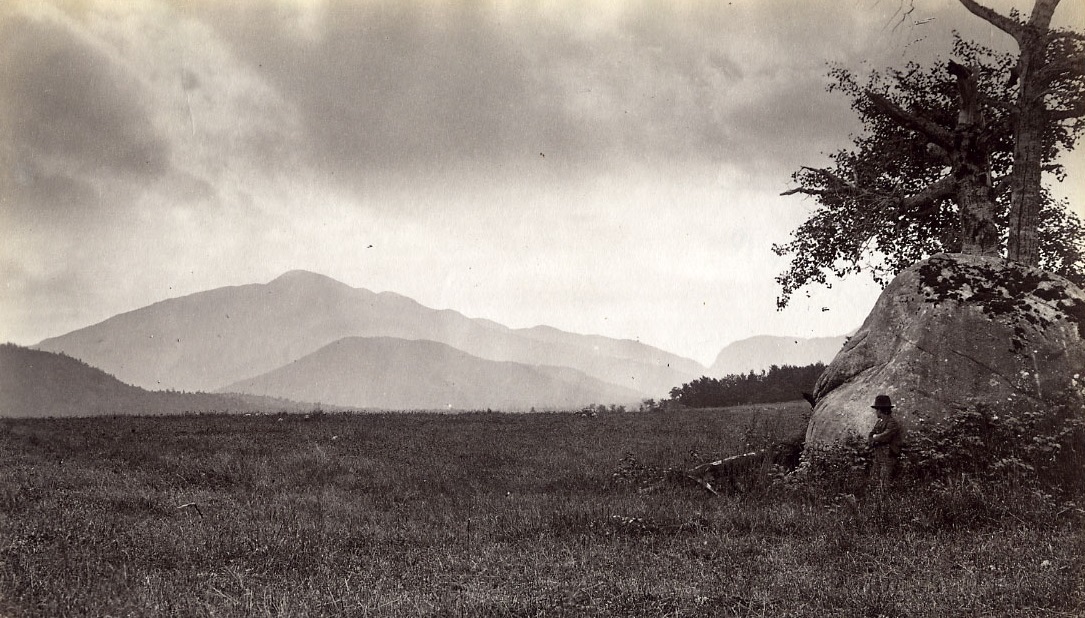

Roosevelt traveled to the Adirondacks to join his wife Edith and children at the remote Tahawus Club near Newcomb, N.Y. Upon arrival he arranged for guides to accompany him and his family for a September 12th trip up Mount Marcy, the tallest mountain in New York State. During this hike, on the shores of Lake Tear-of-the-Clouds, Roosevelt would receive word that McKinley had taken a turn for the worse. A local man named Harrison Hall made the climb to Roosevelt on Mount Marcy with a telegram announcing the president’s now grave condition.

Roosevelt was reluctant to depart immediately and informed his wife that because he had just been there, he would not return to Buffalo until truly needed. However, another telegram announcing that the president was dying banished thoughts of waiting any longer.

Shortly before midnight, Roosevelt traveled by buckboard wagon from the upper camp of the Tahawus Club to the North Creek, N.Y. train station located 35 miles away. By day, this trip would take at least seven hours.

The first portion of the trip would entail three changes of wagons, with fresh drivers and horses each time.

Roosevelt departed from the Upper Tahawus Club, traveling ten miles in two hours to the cabins of the Tahawus Post Office, where he would make his first wagon change.

From here he traveled an additional two hours and twenty minutes over a stretch of nine miles to Aiden Lair Lodge, a popular resort for sportsmen in Minerva, N.Y. Roosevelt once again changed wagons around 3:30 a.m. Mike Cronin, the proprietor of the lodge, would usher the Vice President the final sixteen miles. Despite a dark and slippery road, the two would make it to North Creek in record-breaking time.

His secretary William Loeb, Jr. met Roosevelt at the train station. Loeb delivered the telegram announcing McKinley’s death at 2:15 that morning. Roosevelt had ascended to the presidency on the dark, slippery Adirondack roads hours before.

Roosevelt, who wanted to lose no time getting to Buffalo, departed immediately aboard the fastest locomotive of the Delaware & Hudson Railroad. This trip would not be without incident: in the heavy fog of the morning, there was an accident. The locomotive collided with a handcar, and while the two men aboard survived, it would take an additional fifteen minutes to clear the tracks.** The remainder of the journey was without incident and the party arrived in Buffalo shortly after 1:30 p.m. Upon arrival, Roosevelt stopped at the house of Ansley Wilcox, a Buffalo friend, to have lunch and clean up from the journey. He borrowed “presentable” clothes from Wilcox who was a similar size.

Despite the protests of Wilcox, Roosevelt decided that rather than follow the Cabinet’s decision to hold the inauguration at Milburn House where President McKinley’s body lay, it would be more appropriate to conduct the ceremony at the Wilcox Mansion. He insisted that he would only visit the Milburn House to pay his respects.

After visiting the Milburn House, Roosevelt returned to Wilcox Mansion where he was officially sworn in as president in a small ceremony attended by members of the Cabinet, local dignitaries, and reporters. There were only about forty-three attendants in total.

* Information found in The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris, 1979.

** Information found in Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris, 2001.