Origins of the Adirondack Museum

History is powerful. History can capture the imagination and inspire great events – including the founding of a regional history museum.

The following story illustrates how the lives of two men intersected, how the actions of one served to spark a life-long passion in the second, how the Adirondack museum came to be, and finally how we came to acquire our first truly large artifact – the beloved H.K. Porter Engine.

Harold Hochschild a New York City business executive, long-time seasonal Adirondack resident and lay historian published Township 34, a history of the Central Adirondacks, in 1952. The book furnished a plan and its author guidance and financial support for the Adirondack Museum through the first decades of its development.

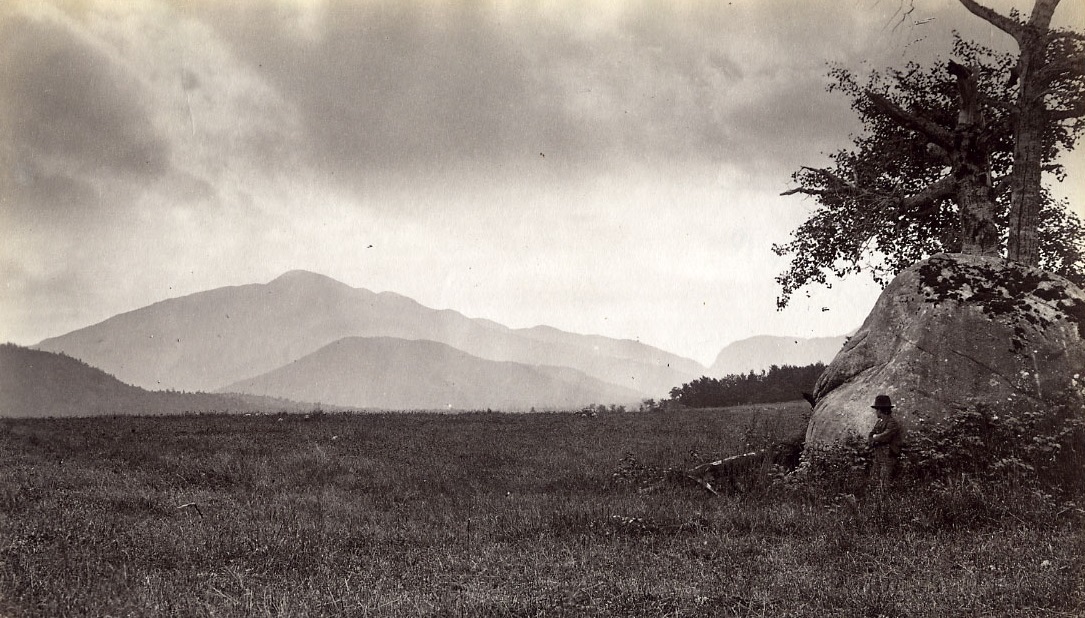

William West Durant was born in Brooklyn in 1850, and educated in England and Germany. His father, Dr. Thomas C. Durant, a vice-president of the Union Pacific railroad, accumulated one of the great fortunes in nineteenth century America. By the 1880s the Durant family had acquired 658,261 acres of Adirondack land and William arrived in the region to manage the family’s investments.

Accustomed to refinement, Durant modeled his Adirondack developments after the baronial hunting estates of European aristocracy. In the process he developed the unique architectural style for what became known as Adirondack Great Camps. Owners of Great Camps acquired vast land holdings, which included wilderness lakes, ponds, and rivers. The camps, actually small isolated villages, were self-sufficient, and often included working farms, greenhouses, icehouses, and even chapels. They were very expensive to build and maintain.

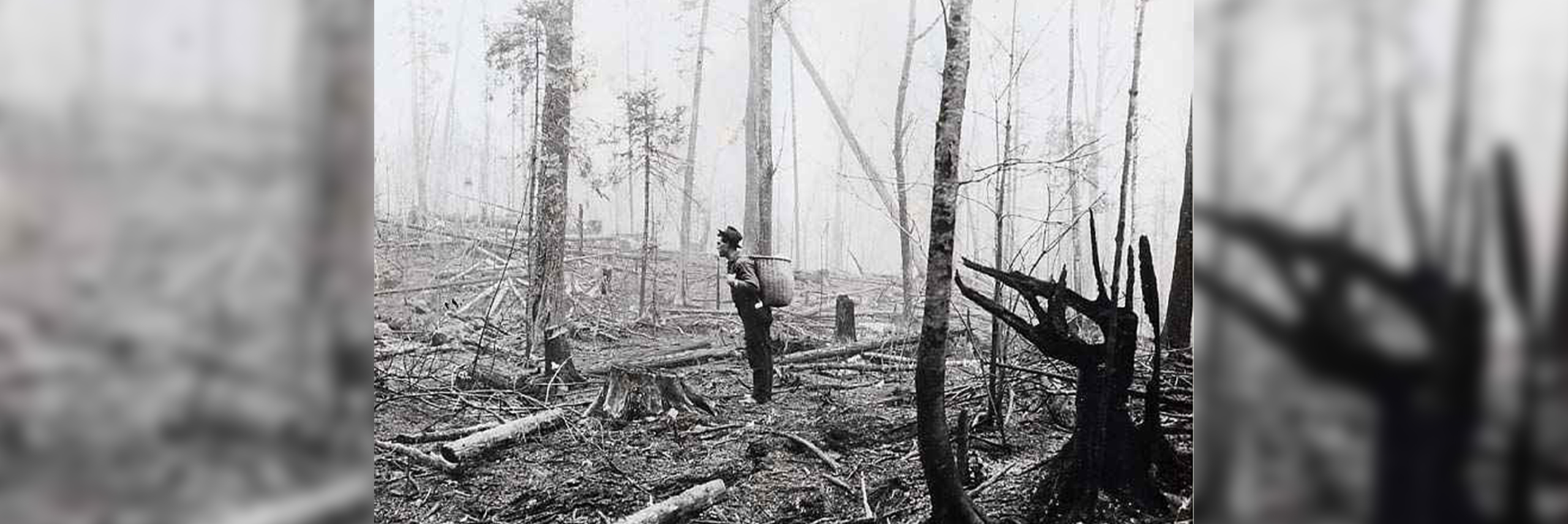

The region’s isolation was a major obstacle to Durant’s development plans. In an effort to attract wealthy tourists, the family built and operated railroads, steamboats lines, roads, sawmills, and a grand resort hotel, the Prospect House in Blue Mountain Lake, New York. By the 1890s Durant was financially overextended.

Despite his growing money problems, Durant began a new project in the spring of 1899; the Eagle’s Nest Country Club. The project was an expensive one, costing nearly $70,000 to build. In the summer of 1900 the country club and its golf course were opened with a series of exhibition matches played by the Scottish professional, Harry Vardon. Vardon’s fee was $500 for the week and a bottle of Scotch whiskey every night. On Saturday night, August 4, to celebrate the opening, Durant gave a dance at the club’s casino, to the music of an eight-piece orchestra, brought from Utica.

By 1904, awash in a sea of lawsuits, including one brought by his own sister, Durant lost control of his Adirondack lands. The assets of Durant’s company were seized by creditors who, in turn, sold the country club’s land to three New York City men: Ernst Ehrman, Henry Morgenthau Sr., and Berthold Hochschild. The three formed a holding company for the land called the Eagle Nest Country Club.

Beginning in 1904 Berthold Hochschild, his wife Mathilde, and his sons Harold and Walter spent June through September every year at Eagle Nest. First the father, then the sons, commuted on the New York Central’s sleeper car from Grand Central Station in New York City to spend weekends at the family’s summer home

Durant’s railroad-steamboat network was still the principal means for getting to the region in 1904. Twelve-year-old Harold Hochschild was captivated by the train and the steamboats. Hoping for a chance to handle the steam-engine’s throttle, he cultivated a friendship with Rassie Scarritt, driver of the H.K Porter Engine on the Marion River Carry Railroad, the shortest standard-gauge line in the world. The engine towed two open passenger cars and a baggage car purchased from the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. in 1900. The total distance covered in the trip was 1300 yards.

Early on Harold began collecting information about the region. He amassed boxes of research materials, letters, Photostats, typescripts, and notebooks containing his penciled notes. His folders, ranging from “Adirondack Iron Works” to “Wild Animals,” are organized by subject in alphabetical order.

Harold’s research notes were the basis for an extensive history of the region. Serious work on the project did not begin until after World War II. Working nights and weekends, Harold researched his book, interviewing as many “old timers” as possible. When Township 34 appeared in 1952, it contained 614 quarto-sized pages, 470 illustrations, 39 maps, 24 appendices, a bibliography, index, and weighed seven pounds without its slipcover. 600 copies were printed.

The publication of Harold Hochschild’s book coincided with William Wessels’ idea of converting the Blue Mountain House, a summer resort high above Blue Mountain Lake, into a museum dedicated to Adirondack history.

The Adirondack Museum was a marriage between a wonderfully scenic site supplied by William Wessels, and the intellectual framework and financial support provided by Harold Hochschild. Many of the museum’s original exhibits were derived from Township 34. The Adirondack Museum opened to the public on August 4, 1957.

Nothing reflects the Adirondack region’s powerful hold on Harold Hochschild’s imagination as much as the museum’s Marion River Carry Pavilion. The pavilion contains the H.K. Porter Engine and passenger cars of Durant’s Marion River Carry Railroad. The train was brought to the museum in 1956, saved from decay in the woods where it had been abandoned.

The Marion River Carry Pavilion includes an automated diorama, known fondly as “the boat train,” that illustrates the history of the complicated, turn-of-the-last -century network of railroads and steamboats that connected the region to the outside world when Harold Hochschild was a boy.

Every year, thousands of museum visitors of all ages linger at the diorama, listening as the recorded “voice” of the display tells the story of the Marion River Carry Railroad – listening to history brought to life.